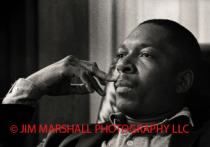

One of the very first prints that Jim ever gave me was a B&W vertical 8” x 10” of a portrait he took of jazz saxophonist John Coltrane in 1960. He gave me “Coltrane” in 1984 and to say I was “woefully ignorant” of jazz music would have been a serious understatement. I think at that time my idea of a great jazz horn player, if I even had one, would have been Chuck Mangione.

To Jim’s eternal credit he never made me feel stupid for what I didn’t know. Rather, he just set about educating me the best way he knew how: show his breathtaking photos, tell intimate stories about the shoot and his feelings for the artist, play favorite and/or relevant album(s) from same artist; wash, rinse, repeat … for literally hundreds and hundreds of images. I used to tell my friends that after a very short while it was like I could “hear” the music just from the sheer strength of Jim’s images.

And, yet, I don’t think I truly grasped how prophetic Jim’s choice of this picture for me was. It's ironic for someone who ended up being managing editor of Windplayer magazine, right? I guess he could tell I was fascinated by the immense dignity and intensity I saw in Coltrane’s eyes and when he played me that mythic version of “Lush Life,” with Johnny Hartman’s unbelievable singing and Coltrane’s incredible tenor and McCoy Tyner’s piano weaving in and around that voice, it brought tears to my eyes, which then made Jim cry (sentimental bastard that he was). And that was that.

As much as it pained him, I think deep down Jim knew he was never going to be accepted into “the white man’s world” and that’s why artists like Coltrane and Miles Davis touched him so deeply. The only child of a single mom, and Assyrian-Armenian to boot, Jim was brought up in serious poverty. His mom held three jobs at times, including working at a laundry, to keep a roof over their heads. Jim had the acute vision and powerful yearning of someone who was always going to be on the outside looking in, no matter how many world-beating shots he made, or all-access passes he acquired.

What comes around goes around

We thought it appropriate to talk a bit about Jim’s relationship to black jazz artists and their affinity for him as Black History Month intersects with this week’s Presidents’ Day. Most people who know of Jim’s legacy think his career shooting musicians began in the folk and rock worlds of the early ’60s. His real break came some years earlier photographing relatively unknown but crucially important black musicians in North Beach jazz venues such as The Jazz Workshop.

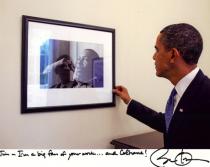

There was a major difference between the persona Jim showed the public – ultra conservative, gun-toting, racism-spewing, lower-class hating, right-wing nut job – and the real Jim, who was the perpetual outsider looking intensely at the world from behind the mask. Lucky for all of us, Jim learned to take the mask off and hide behind that Leica M4 instead; that was the Jim who loved Coltrane, Miles, Thelonious Monk, too many to name really, and who was loved in return. After a gig one evening in San Francisco in 1960, Coltrane asked Jim, “How do you get to Berkeley?” He had a meeting with the San Francisco Chronicle’s legendary music critic Ralph J. Gleason at his Berkeley Hills home the next day and he had no clue how to get there. Gleason’s bona fides are too numerous to mention (first jazz critic at a U.S. daily newspaper, came up with Monterey Jazz Festival concept, gave Jann Wenner $1,500 to start “Rolling Stone, etc. etc.). Jim was well aware of Gleason’s crucial role connecting music, culture and politics and, sensing the import of the moment, he offered to drive Coltrane to Gleason’s and was allowed to stay and shoot … and the rest is history. For the better part of two decades a bit of that history has lived on my walls, lucky gal that I am. And now a similar Coltrane portrait (an 11” x 14” horizontal version) lives on a wall at the White House. Jim has a wonderful photo snapped by a White House photographer of President Obama studying the Coltrane portrait intently and on the mat overlay the President has written: “To Jim – I’m a big fan of your work … and Coltrane!”

I will never forget the look on Jim’s face when he stood in the gallery that was his hallway and looked at that photo of his President studying the Coltrane portrait; there was no mask, no barrier, I just saw awe, humility, and incredible color-blind, bipartisan joy. Jim looked like he had finally come home.

- Jim Marshall Photography LLC Newsroom blog

- Log in to post comments