I was reading the New York Times Sunday magazine recently and came across a lovely little piece on Ravi Coltrane, the son of the brilliant musicians, jazz saxophonist John Coltrane and composer/pianist Alice Coltrane; the piece touted Ravi’s new album: “Spirit Fiction,” and right at the beginning of the story by Zachary Woolfe, I was thrilled to read the following: “ ‘Ambition sometimes gets a little out ahead of you,’ Ravi Coltrane said. He was sitting in his living room in Brooklyn, next to his son’s tiny drum kit, talking about his new album, “Spirit Fiction.” ‘You start imagining more than you can actually pull off, and you cross that line from possibility into impossibility.’ “On the wall nearby was a framed photo of Barack Obama standing in the White House gazing at a black-and-white photo of another musician, a saxophonist like Ravi. ‘To Ravi,’ it is inscribed. ‘From a huge fan of your father’s.’ ” Of course, I immediately recognized the photo reference and, though I have no way to corroborate it, I deeply feel that the writer is describing the same photo taken by a White House photographer of President Obama looking at Jim Marshall’s very famous 1960 black-and-white portrait of John Coltrane that I blogged about in “Jim, John Coltrane and President Obama” in early 2011. Here’s an excerpt for those who might have missed it:

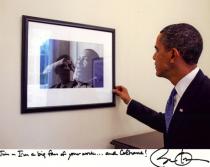

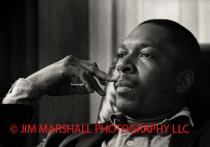

“There was a major difference between the persona Jim showed the public – ultra conservative, gun-toting, racism-spewing, lower-class hating, right-wing nut job – and the real Jim, who was the perpetual outsider looking intensely at the world from behind the mask. Lucky for all of us, Jim learned to take the mask off and hide behind that Leica M4 [and M2s] instead; that was the Jim who loved Coltrane, Miles, Thelonious Monk, too many to name really, and who was loved in return. “After a gig one evening in San Francisco in 1960, Coltrane asked Jim, “How do you get to Berkeley?” He had a meeting with the San Francisco Chronicle’s legendary music critic Ralph J. Gleason at his Berkeley Hills home the next day and he had no clue how to get there. Gleason’s bona fides are too numerous to mention (first jazz critic at a U.S. daily newspaper, came up with Monterey Jazz Festival concept, gave Jann Wenner $1,500 to start “Rolling Stone, etc. etc.). Jim was well aware of Gleason’s crucial role connecting music, culture and politics and, sensing the import of the moment, he offered to drive Coltrane to Gleason’s and was allowed to stay and shoot … and the rest is history. “For the better part of two decades a bit of that history has lived on my walls, lucky gal that I am. And now a similar Coltrane portrait (an 11” x 14” horizontal version) lives on a wall at the White House. Jim has a wonderful photo snapped by a White House photographer of President Obama studying the Coltrane portrait intently and on the mat overlay the President has written: “To Jim – I’m a big fan of your work … and Coltrane!” “I will never forget the look on Jim’s face when he stood in the gallery that was his hallway and looked at that photo of his President studying the Coltrane portrait; there was no mask, no barrier, I just saw awe, humility, and incredible color-blind, bipartisan joy. Jim looked like he had finally come home.”

A Supreme Connection

One of the many classic albums that Jim turned me on to back in the day was John Coltrane’s incredibly moving, “A Love Supreme,” considered one of the greatest jazz albums of all time. His love of that recording was one of the first ways I understood that, while Jim was far from church-y, he did have a tremendous sensitivity and a sort of spiritual streak; with me Jim loved to show a belief in life-affirming connections and coincidences, influences and powers beyond our control. And he delighted in discovering them. It always gives me such joy to remember that moment in 2009 when I was standing with Jim in his hallway watching him watching me appreciate his Coltrane-Obama moment captured so profoundly. Jim’s delight was palpable; it was the joy of knowing that he had played a small but praise-worthy role in capturing moments that inspire and endure far beyond what he or I or John Coltrane or Ralph Gleason could have ever predicted. Deep down I know that impact was Jim’s dream all along, to make a difference, to love supremely and be loved in return.

- Jim Marshall Photography LLC Newsroom blog

- Log in to post comments